Wealth-X, an Altrata company, recently analyzed the giving habits of ultra high net worth (UHNW) individuals around the world to gain a better understanding of how philanthropy has evolved in recent years. In this context, UHNW individuals are people with a total net worth of at least $30 million. The results of the analysis indicate that global philanthropic activity has steadily increased, especially in light of events like the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are also some key differences between giving patterns between regions and among different tiers of wealth. Some regions, such as Asia, are beginning to formalize much of their philanthropic efforts through the consolidation of new organizations.

UHNW individuals in some regions also prefer different causes than those in others. For example, healthcare ranks in the top six industries of UHNW donors in North America and Asia, but not in Europe, where the public sector plays a more prominent role in the provision of healthcare services. Philanthropy aimed at improving education is also more popular in Asia than it is in other regions.

In this article, nonprofits and fundraisers will learn how they can act on these trends and what changes they can expect from the global philanthropic movement in the coming years. We will also cover the latest trends in strategic giving—a trend in which philanthropists are working with governments and nonprofits for a more pronounced impact.

How the Scale of Philanthropic Giving Has Changed

The past few years have seen a general uptick in philanthropic giving, particularly from UHNW individuals. According to Wealth-X’s report, Ultra High Net Worth Philanthropy 2022, total giving by the ultra wealthy rose by 4.1% in 2020, outpacing the growth in giving from non-UHNW, which rose by only 2.9%.

These increases in giving were characterized by collaborations between grant-makers and donors. They may also be the result of an increase in the amount of wealth accumulated by UHNW philanthropists. According to the report, the global UHNW population grew 1.7% in 2020 to 295,450 individuals.

The combined net worth of this population increased by 2% to $35.5 trillion.

Nonetheless, leaders from Global Philanthropic say that although there has been an increase in philanthropic giving, it is not at a level needed to address global challenges. Founded in Hong Kong in 2002, Global Philanthropic provides strategic assistance to corporations, philanthropists, and fundraisers around the world to help them make a greater impact through giving.

According to Ben Morton Wright, President and Group CEO of the Global Philanthropic Worldwide Group of Companies, philanthropic giving at 2% of GDP has long been the gold standard. That level of giving needs to increase significantly to accommodate a rising gap between rich and poor: “We’re encouraged that giving is increasing among UHNW individuals, but the gap between rich and poor is getting greater—the wealthy are becoming wealthier. Giving needs to accelerate on a massive scale. We want to see double-digit growth.”

Further growth in philanthropic giving may be necessary for communities to overcome local, regional, and global problems. This was evident during the pandemic.

Many governments struggled to come together to address issues raised by the pandemic, such as economic recession, job loss, and supply chain challenges. Meanwhile, philanthropic organizations and wealthy individuals successfully coordinated their efforts to deliver help where needed via foundations and nonprofit organizations.

According to Pam Davis, Senior Consultant and President of Global Philanthropic Europe, “Over the past two years, the demands on government continued to skyrocket. Encouraging wealthy individuals to bridge the gap is critical. Thankfully, many people felt that they wanted to contribute, and we felt that we came together in ways that we hadn’t before.”

In the future, philanthropic efforts from wealthy individuals could be crucial to overcoming future problems that governments can’t solve on their own: “We hope that will continue to be the case,” says Davis.

Popular Causes for Donors

Many of the most popular causes for donors relate to recent events. However, some regional giving trends suggest long-standing causes, such as education, are still among donors’ top priorities.

Pandemic Relief

Not surprisingly, many donors were focused on pandemic relief efforts in 2020 and 2021, especially in regions where governments struggled to keep pace with the needs of their populations. For example, the Wealth-X report found that healthcare and social services were among the seven most prevalent philanthropic causes among UHNW donors in North America, Europe, and Asia.

Education

However, Education continues to remain one of the top philanthropic causes among these donors. Education was a selected cause for 55.8% of North American respondents, 47.3% of European respondents, and 62.0% of Asian respondents.

Ukraine

The war in Ukraine is likely to be a dominant cause for philanthropic giving in the coming months and years. As this is a new crisis, data on UHNW individuals’ philanthropic efforts are still forthcoming. However, several wealthy individuals have already made significant humanitarian donations to help Ukrainian refugees and people still struggling within the country.

According to a report by Fortune, Ukraine had already received nearly $900 million in donations from wealthy individuals as of April 15th, 2022. Meanwhile, a report by Devex, a media platform for the global development community, indicated that their funding platform had recorded about $28 billion in commitments related to Ukraine as of April 28th, 2022.

UN Sustainable Development Goals

Finally, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals have been an important cause for donors in recent years. However, there is concern that the scale of the world’s sustainability needs is too large for philanthropists to handle alone. There needs to be better coordination and understanding between states and individuals, as this would allow gifting to be simpler and work more effectively on a global scale.

As Pam Davis puts it, “sustainability has to be more than a tick box.”

Regional Giving Trends

There is plenty of overlap between the philanthropic interests of the wealthy in different regions. However, there are some differences between giving in North America, Europe, Asia, and what Global Philanthropic refers to as “The Global South” as well.

Giving Trends in North America

North America has long led the world through its philanthropic initiatives. According to Ben Morton Wright, the “gold standard of giving in the world is the US. Many successful Americans are focused on giving away their wealth during their lifetimes.”

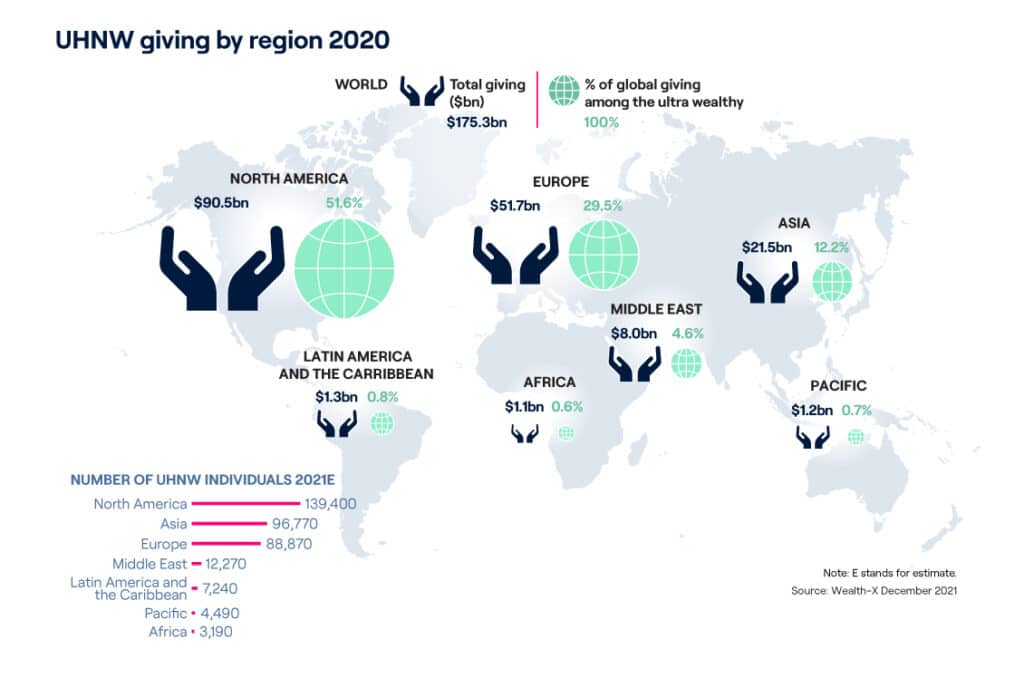

More than $175 billion was given to philanthropic causes in 2020 and Northern America accounted for more than half of that, giving $85 billion in total. This includes $90.5 billion among North America’s 139,400 UHNW individuals, according to the Ultra High Net Worth Philanthropy 2022 report by Wealth-X.

Evidence from the Wealth-X report and responses from the experts from Global Philanthropic suggest that there is an emergence of heightened philanthropic activity in other regions, most notably Asia.

Giving Trends in Asia

According to the Wealth-X report, Asia is the world’s second-largest ultra wealth region, with a UHNW population and total net worth approximately 15% larger than that of Europe.

The average age of ultra-wealthy donors in the region is 8 years younger than those in North America. The share of wealthy donors under 50 is also three times higher than in North America. Much of this wealth has been generated among wealthy individuals engaged in the technology industry, which accounts for 10.4% of donors in the region.

The most popular philanthropic cause in Asia is education. Education accounted for more than half of donations (62%) in 2020. However, the pandemic has accelerated giving toward healthcare.

UHNW giving Asia only accounted for 12% of the global share in 2020. However, there is evidence that Asia is emerging as a center for increasing philanthropy. This may be due, in part, to the rise of new philanthropic and non-profit organizations.

According to Ben Morton Wright, the giving trends in Asia are encouraging: “Twenty years ago, there were virtually no professional philanthropic bodies in the region. The surge of these types of organizations in Asia has gone through the roof.”

Wright notes that Asia is at a different stage of philanthropic development than other regions.

In the west, philanthropy is strategic. There are signs that Asian philanthropists are moving toward a more strategic form of philanthropy, but much of the philanthropic giving we see in the region is through family businesses that have been passed down through many generations, “and so there’s an intergenerational discussion,” said Wright.

Giving Trends in Europe

According to the Wealth-X report, Europe’s ultra-wealthy accounted for 30% of total UHNW giving, at $52 billion. The cumulative net worth of the region’s ultra-wealthy class is substantial, but it is still about 30% lower than that of North America. Cumulative net worth in Europe has also seen slow growth in recent years

Nonetheless, there is a more balanced age distribution of UHNW donors across Europe. A significant portion of European donors (12.5%) are younger than 50. This can be partially explained by younger, more dynamic markets in eastern Europe and the Nordics.

Like North America, Europe has a long tradition of unrestricted giving. It also has established philanthropic and nonprofit organizations that make an impact globally. The biggest trend in this region is that philanthropists and philanthropic organizations are beginning to coordinate more effectively to tackle global problems.

According to Pam Davis, “In Europe, we’ve seen unrestricted giving coming to the top. Many of the big philanthropists, trusts, and foundations have come to understand how important funding is for the lifeblood of the organization, so we are seeing more of them work together to solve some of the biggest problems. The cloak of invisibility around these donors is starting to fade away.”

European philanthropy is noteworthy due to its transparency. There is much more collaboration between UHNW individuals, governments, and nonprofits than in some other regions, and individuals tend to be much more transparent about where and how much they are giving.

Giving Trends in the Global South

Significant increases in philanthropic giving in places like Europe and North America are encouraging. However, these regions have long dominated the world of philanthropy. The rise in philanthropy within regions that have been sidelined historically could have an even greater impact on communities.

For example, countries located in the southern hemisphere, including many developing economies, have not always been recognized for their philanthropic giving. Pam Davis and Ben Morton Wright, among others, generally refer to these regions and the countries within them as “the Global South.” According to the London School of Economics, this term “has been a general rubric for decolonized nations roughly south of the old colonial centers of power.”

Global Philanthropic notes that there is a “historically unequal power dynamic that exists between philanthropic organizations in the Global South (including NGOs and social enterprises, grantmakers and grant recipients) and resource-rich foundations of the Global North.” This power dynamic is underlined by the control foundations in the Global North have over funding allocation as well as difficulties organizations in the Global South encounter during grantmaking processes.

There is an abundance of wealth in many areas of the Global South, as well as wealthy individuals who wish to donate to philanthropic causes. As such, this power dynamic may be hindering the Global South’s ability to contribute and limiting global philanthropic impact overall.

According to Pam Davis, “The lack of representation and recognition among the Global North of the Global South has been alarming. The Global South has so much to contribute; they just have fewer resources to do so. The global South needs to be setting the agenda rather than being on the agenda.”

Davis suggests that the philanthropic community reassess its attitude toward who gets to contribute and how

“It can’t just be a very small group of people who all look alike,” says Davis. “We all recognize that we need many voices at the table, especially those people who are living through challenges. They have a lot of knowledge and understand the problems.”

Practical Strategies for Engaging Donors

Most UHNW and HNW individuals will likely be prepared to give to philanthropic causes in the coming years. They generally engage with multiple organizations at a time.

The challenge is two-fold: both engaging wealthy individuals to be donors and retaining them in the long term. Organizations must be able to provide each donor with a suitable philanthropic journey. Through research and practical strategies, organizations can minimize errors, improve efficiency, and create a bigger impact.

Here are a few strategies for engaging donors over the next few years.

Grassroots Impact

One strategy for engaging these donors is to point out that large NGOs and international organizations are increasingly bureaucratic. Although they receive significant funding, including government funding, their bureaucratic operations may limit their impact. UHNW and HNW individuals may have a greater and quicker impact with medium- to small-sized organizations focused on the grassroots level.

According to Ben Morton Wright, philanthropy should not be transactional if it is to be effective. Instead, it should work strategically to target the root causes of problems and be scalable. These are concepts that established organizations can export to emerging philanthropic regions.

“In the West, philanthropy is well understood as strategic,” says Wright. “You can’t necessarily solve global poverty and hunger, but you can make an intervention that can be scaled up. Philanthropy is much more transactional in other regions, but strategic philanthropy is beginning to emerge elsewhere, and that excites us.”

Storytelling as Means of Engagement

Pam Davis recommends that philanthropic organizations tell their stories to encourage more engagement.

“When engaging high net worth individuals, one of the things we find is that many organizations are still not telling their stories, at least not in a way that’s resonating,” says Davis.

In other words, it’s important to discuss your case for donations and the impact they can make on communities. However, stories must also be tailored to the person to whom you are pitching.

Prospect research is key to generating insights into wealthy individuals, so you can tailor stories to match your unique prospects and their interests. Donor intelligence allows you to effectively qualify, cultivate, and solicit the best prospects by building a meaningful and emotional connection between their goals and your mission.

Leveraging Data and Networks

Finally, philanthropic organizations, NGOs, and nonprofits can leverage data, donor intelligence, and their networks to efficiently engage with donors at scale. Data intelligence providers like Wealth-X are specifically designed to help these types of organizations identify and connect with the world’s wealthiest individuals. Not only does it provide data about UHNW individuals’ wealth and investments, but it also provides information about their interests, personal projects, and unique giving histories.

According to Pam Davis, Wealth-X could help organizations identify donor networks much more effectively.

“Wealth-X could help to map these networks and get you introductions to potential donors.”

“Our experience has been that you might know a few people who give, but you won’t know their entire network,” says Davis. “Organizations in some regions may not be as developed as those in the U.S. or U.K., so their networks are quiet. Wealth-X could help to map these networks and get you introductions to potential donors.”

Overall, research supports sustainable growth, allowing organizations to reach prospects organically, but it can be challenging without the right tools. Networks are becoming increasingly international, and there is extensive cross-over between peer-to-peer networks, institutions, and corporations. This makes donor research more complex and time-consuming than it may have been in the past.

Sometimes, it is essential to discover new connections through your network. Other times, organizations simply need a better understanding of their existing networks. Tools like Wealth-X help optimize networks, so you can lean on them when donors are needed.

“It comes down to working your network and finding those individuals who connect with your story,” said Pam Davis.

New Philanthropic Models

Grant-making has also changed over the past few years. There are more sophisticated mechanisms for gifting beyond simple donations.

For example, social investments, social bonds, donor-advised funds (DAFs), and, most recently, crypto-currency gifting are all viable ways to make an impact. The philanthropic sector needs to understand these new models, and philanthropic organizations are in an ideal position to educate them.

Conclusion

While there is evidence that global giving will increase, the need for gifts from wealthy individuals will also continue to grow. Thankfully, the culture of giving is also changing. HNW individuals are much more participative and collaborative than they have been in the past, and strategic philanthropy is becoming more accepted in regions around the world.

Networks are now key to engaging HNW individuals. Organizations must be able to conduct mapping exercises so they can fully understand their donor and board networks and the interests of new potential partners and donors within them. Understanding cultural differences in giving will also be key, as it can help organizations cater to donors’ motivations.

There are significant opportunities for philanthropic organizations to leverage prospect research to build stronger, more targeted stories and connect with their donors. Using research to shape communications will be essential moving forward, especially for those organizations fundraising across borders.